In the contemporary global financial landscape, the concept of ethical banking has emerged as a critical imperative rather than a peripheral concern.

ISLAMIC FINANCE

In the contemporary global financial landscape, the concept of ethical banking has emerged as a critical imperative rather than a peripheral concern.

As economies become increasingly interconnected and vulnerable to systemic shocks, the demand for financial institutions that operate with integrity, transparency, and social responsibility has intensified. This shift is particularly pronounced among younger generations, including Millennials and Gen Z, who prioritise values such as environmental stewardship, fairness, and accountability in their financial decisions. Ethical banking, therefore, is a strategic necessity for sustainable economic development.

The global financial crisis of 2007-2009 serves as a stark illustration of the consequences of a financial system divorced from ethical constraints. The crisis was precipitated by excessive leverage, widespread use of complex derivatives, and a detachment from real economic activity. According to the IMF, the crisis resulted in the loss of trillions of dollars in global financial assets and triggered a prolonged period of economic instability. The collapse of major financial institutions and the subsequent erosion of public trust underscored the fragility of interest-based systems that prioritise speculative gains over productive investment.

In contrast, Islamic banking demonstrated notable resilience during this period. Rooted in principles that prohibit interest (Riba), excessive uncertainty (Gharar), and speculative transactions, Islamic finance emphasises asset-backed lending and profit-and-loss sharing. These ethical constraints inherently limit exposure to the types of toxic assets and high-risk instruments that exacerbated the global crisis.

A 2015 IMF working paper highlighted that Islamic banks, particularly in Pakistan, were less susceptible to deposit withdrawals and maintained lending activity during periods of financial stress. This resilience was attributed to their conservative balance sheets and alignment with real economic activity.

It is important to recognise that ethical banking is not exclusive to Islamic finance. Across various regions, secular institutions have adopted similar principles to address the shortcomings of conventional banking.

Triodos Bank in The Netherlands, for example, finances only sustainable enterprises and operates under a governance model that prioritises social impact over shareholder profit. The Co-operative Bank in the United Kingdom has implemented a customer-led ethical policy that excludes financing for fossil fuels, arms and companies with poor human rights records. These institutions demonstrate that ethical banking can be both financially viable and socially beneficial, regardless of religious orientation.

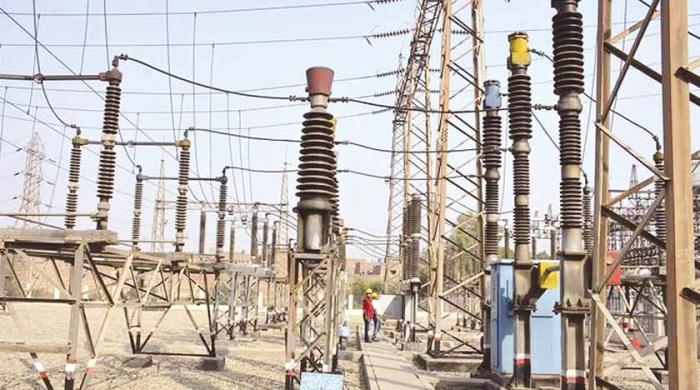

In Pakistan, the strategic shift towards Islamic banking reflects a much broader commitment to ethical finance. The country faces significant economic challenges, including currency depreciation, fiscal deficits and structural development needs. In this context, a resilient and trustworthy financial sector is essential for long-term stability.

Islamic banking, with its emphasis on fairness, transparency and real economic activity, offers a robust framework for ethical finance

The adoption of Islamic banking models by several leading institutions and the complete transformation to an Islamic model by one of the country’s major banks signify a deliberate move toward financial practices aligned with national development goals. Faysal Bank stands out as a pioneering example of this transformation. Its journey from a conventional bank to becoming one of Pakistan’s largest fully Islamic banks is widely regarded as a benchmark for ethical banking in the region. In fact, since completing its conversion to a fully Islamic bank, Faysal Bank has expanded to nearly 900 branches across 300-plus cities in Pakistan.

Research by Morgan Stanley indicates that 95 per cent of millennials express interest in sustainable investing, while Gen Z is projected to experience a fourfold increase in wealth over the next decade. These consumers are discerning and values-driven, seeking financial institutions that reflect their ethical priorities. They are more likely to engage with banks that offer transparent, non-exploitative products, finance housing and small businesses through asset-backed contracts and provide clear disclosures. Ethical banking, in this regard, is not only a moral imperative but also a competitive advantage.

The broader implications of ethical banking extend beyond individual institutions and national borders. Finance is not merely a technical system; it is a social infrastructure that influences livelihoods, enterprise and societal well-being. Banking models that prioritise ethical considerations are more likely to foster inclusive growth, reduce systemic risk and build public trust. The convergence of Islamic and secular ethical finance models suggests a growing recognition of the need for financial systems that serve the public good rather than narrow interests.

Ethical banking is now understood to be the foundational element of a stable and inclusive economy. The lessons of past financial crises, evolving consumer expectations and strategic shifts within national financial systems collectively point to the necessity of banking models that operate with integrity and purpose.

Islamic banking, with its emphasis on fairness, transparency and real economic activity, offers a robust framework for ethical finance. When complemented by secular initiatives and supported by effective regulation, ethical banking can become a transformative force in the global financial ecosystem.

Pakistan’s ongoing transition to Islamic finance exemplifies this potential, positioning the country as a proactive participant in the global movement towards ethical and resilient banking.

The writer is a freelance contributor.