Horror stories by Anglophone writers from Pakistan have often been regarded as a somewhat niche category. They have become a fertile space for creative experimentation, with women writers driving it forward through their chilling tales of the unknown. Read on...

fiction

The language of fear is universal - a visceral response to a real or perceived threat to our wellbeing. Yet, not all fears are created equal.

The spine-tingling terror of the inexplicable always takes precedence, seeping into our consciousness and wreaking havoc on our hearts and mind. This notion is echoed in the words of American supernatural, sci-fi and horror fiction author H P Lovecraft, who described the terror of the unknown as the “oldest and strongest kind of fear.”

Tales of horror capitalise on the timeless, universal and utterly unpredictable nature of human fear. Owing to their undeniable sophistication, the works of Mary Shelley, Stephen King, Bram Stoker and H P Lovecraft continue to attract a wide readership. Apart from being enthralled by the timeless and formidable works of these Western literary giants, local audiences are equally captivated by South Asian horror fiction.

Be that as it may, horror stories by Anglophone writers from Pakistan have often been regarded as a somewhat niche category. While the genre isn’t as widely acknowledged on a global scale, it has become a fertile space for creative experimentation, with women writers driving it forward through their chilling tales of the unknown.

Widely regarded as Pakistan’s first woman editor and magazine publisher, Zaib-un-Nissa Hamidullah was also the author of minimalistic stories that capture the bittersweet realities of old age, rural life and Pakistan’s formative years as a nation. Her collection of short stories ‘The Young Wife and Other Stories’, includes two tales that fall neatly within the horror genre. ‘Wonder Bloom’ features a newly married couple who make a quick pit stop at a luxurious garden in Sindh while returning to Karachi from their honeymoon. As the duo wanders through this oasis-like garden, the caretaker recounts a chilling account of the human sacrifices required to sustain its splendour. In another story, titled ‘Motia Flowers’, Hamidullah weaves together strands of memory and heartbreak into a haunting tale of tragic love. Both stories benefit from quiet restraint that adds to their mystique.

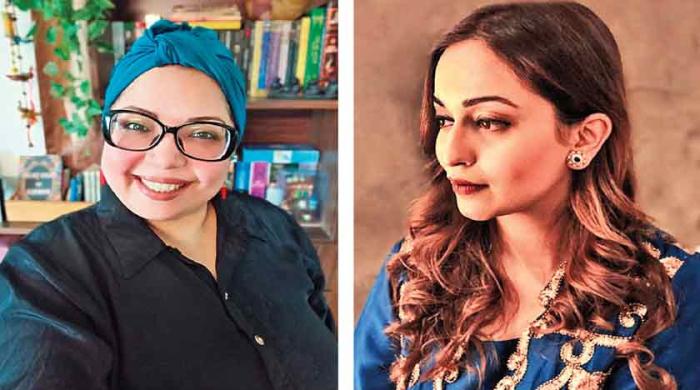

Any discussion on the quintessentially ‘Pakistani’ horror story feels incomplete without a careful appraisal of Ayesha Muzaffar’s contributions. Her earlier books - titled ‘Jinnistan’ and ‘The Bhabhis of Lahore’ - offer short narratives about paranormal entities that exist within our realm. At no point do these spiritual entities come across as the implausible products of a wildly imaginative mind. Instead, the element of horror stems from the quiet terror that lurks within the mundane. Ordinary people find themselves at the heart of inexplicable hauntings. A supernatural world that we don’t always fathom remains at the emotional core of ‘Jinnistan’ and ‘The Bhabhis of Lahore’. Roman Urdu figures prominently in dialogue - a technique that is at once unsettling yet familiar. These creative choices naturally appeal to audiences who are drawn towards narratives with a local flavour.

In her latest offering, ‘The Haunting of Dr Rahim-ud-Din Shamsi and Other Unsettling Tales’, Muzaffar expands her oeuvre with three novellas written in the tradition of horror fiction. The titular piece revolves around a dentist born with six fingers who is haunted by a childhood prophecy of doom. Dr Shamsi encounters a plethora of unusual incidents at his clinic, which lead him to question the difference between scientific knowledge and the unseen realm.

A woman’s grief over her first husband’s unexpected demise is at the heart of ‘Finding Faraz’, the second story in Muzaffar’s new book. The strength of these novella-length tales lies in the steady build-up, even if their denouements appear to be somewhat restrained. Moving beyond the unassuming subtlety of the first two novellas, ‘The Possession of Bareera Khurram’ benefits from spooky restraint and a far more satisfying conclusion. All in all, Muzaffar’s new stories are immensely readable and compelling.

‘Dark Tales of Wonder’, Maliha Rao’s debut collection, doesn’t just dwell upon the dark and distressing possibilities of interaction with supernatural forces. Instead, it seeks to peel back the layers of complexity surrounding them. The dark forces who lurk through the pages of Rao’s first book don’t exist merely to terrify readers; they also serve as a reminder of the importance of coexistence between humans and the unseen. Rao’s supernatural beings emerge not just from a vivid imagination but also from extensive research - a testament to the author’s depth of knowledge on the subject. Many of her stories, such as ‘Crumbs and Creatures’ as well as ‘The Wrath of Boyo’, are memorable and endearing for their profoundly empathetic portrayal of supernatural beings.

Whenever I’ve compiled multi-authored anthologies, I’ve made a concerted effort to include horror stories, both to diversify and enrich the collections. Many of them have invariably been written by women. ‘The Unwritten Story’, penned by journalist and editor Wajiha Hyder, isn’t a conventional ghost story, but it embodies the spirit of one. Published in ‘The Stained-Glass Window: Stories of the Pandemic from Pakistan’, which I co-edited in 2020, Hyder’s narrative explores the troubled mind of a cynic who seeks to escape the duplicities of the world.

Volume I of ‘Tales from Karachi’, which I compiled and edited in 2021, also consists of three horror stories. These stories aren’t rooted in local myths and folklore, and are considerably shorter than the tales published by Muzaffar and Rao. Even so, they are a constant reminder that ghost stories still resonate with both authors and readers alike.

Horror stories don’t need to be laced with sensational elements. Journalist Maheen Usmani’s short story ‘Shadow’, published in ‘Tales from Karachi’, serves as welcome proof of this belief. Using the ingredients of silence and isolation to great advantage, Usmani offers a compelling story about real and imagined fears. Hafsa Maqbool’s ‘Tayyaba’s Tree’ features a conversation between an elderly Hamza and the eponymous Tayyaba, his deceased wife. Rooted in the time-honoured belief that love never dies, Maqbool’s tale is a poignant reminder of the porous boundaries between the earthly and the divine. The distance between both realms can only be traversed through the eagerness of the heart.

Huma Sheikh’s ‘The Banyan Tree’ also navigates the delicate boundaries between the earthly and heavenly realms. Little Rani eavesdrops on a conversation between the elderly Sahiba Bibi and her sister about angels, jinns, trees and the unbearable despair of loneliness. However, the adults cannot see the child who gazes at them through “huge, luminous eyes.”

Neither Maqbool nor Sheikh exploit the genre for superficial scares and mindless melodrama. Instead, their stories offer a candid and moving exploration of the perils of isolation. Beyond the shallow thrills and low-stakes drama, the horror genre seeks to map the contours of fear. It allows us to examine our long-standing anxieties about life and death from a comfortable distance. This can be a cathartic yet insightful endeavour. Above all, horror fiction relies heavily on escapist fantasies and pulls us away from the mundane realities of our less-than-perfect worlds.

A law graduate from SOAS, London, Taha Kehar is the author of three novels, including ‘No Funeral For Nazia’. He can be reached at [email protected]