Celebrated every year on December 18th, Kissan Day honours the invaluable contributions of farmers to Pakistan’s economy and food security. You! takes a look…

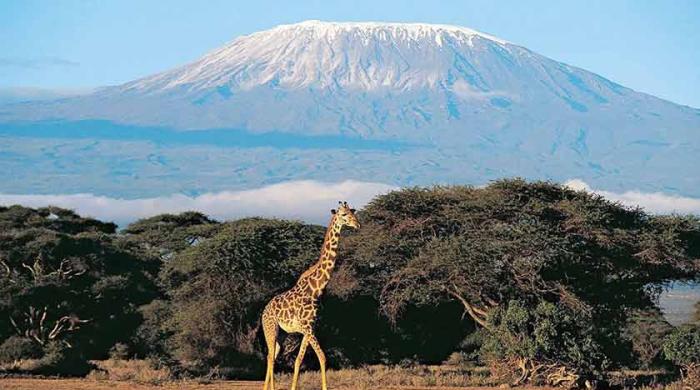

While travelling on highways from one city to another, or from one province to another, we can see and notice the beauty of Pakistan’s farmland. The lush green fields, golden wheat, vibrant mustard flowers and sprawling banana plantations paint a picture of abundance. Men and women labour from dawn to dusk, cultivating the land, tending the crops and nurturing the hope of a better tomorrow. This sight, however, is not just a symbol of prosperity it is also a testament to the resilience of Pakistani farmers.

But this beauty hides the silent struggles underneath. It also hides the fear every farmer carries: What if next season’s rain destroys everything? Climate change has rewritten the story of Pakistani agriculture. And sadly, farmers are paying the price.

We grew up reading in our school textbooks that Pakistan is an agricultural country. Agriculture has been the backbone of Pakistan’s economy since its inception. It provides food, employment, and sustenance to millions of people across the country. Yet despite its critical role, the sector faces challenges that threaten not only the livelihoods of farmers but also the nation’s food security. According to World Bank data, agriculture’s share in Pakistan’s GDP was approximately 43.19 per cent in 1960 and it has dropped to around 23.5 per cent in 2024. This decline reflects a shift in the economy, but it also underscores the urgent need to protect and empower the farmers who feed the nation.

Kissan Day

The tragedy of lost crops is a recurring nightmare for farmers. When floodwater sweep across fertile fields, the hard work of months vanishes in days. Their dreams, investments and efforts are washed away. On such days, farmers desperately need government support, technical assistance and access to affordable quality seeds and equipment.

Celebrated every year on December 18th, Kissan Day or National Farmers’ Day was officially initiated in 2019, following national advocacy by farmers’ groups and private-sector partners to acknowledge the role of small-scale farmers. The day honours the invaluable contributions of farmers to Pakistan’s economy and food security.

It also serves as a reminder to recognise challenges faced by the farmers and to implement policies that protect their rights and livelihoods.

Through the eyes

of farmers

Hanifa Khatoon, a small-scale farmer and mother of four, represents the silent strength of rural women. Working from dawn to dusk, she cultivates her small piece of land to support her children’s education and secure a better future for them.

Hanifa shared her personal struggles: the constant water shortages, the long wait for canal water that rarely reaches her village and the heavy cost of relying on tube wells. She spoke about how difficult it is to purchase quality seeds often buying them at high prices from local markets because no government facilitation, subsidized seeds, or easy loans are available for women farmers.

She also highlighted the physical toll of farming, explaining how she continues working even when unwell, because missing a day means losing precious income. Hanifa requested the government to ensure health facilities near farming communities, especially for women who carry both agricultural and household burdens.

For her, farming is not just livelihood, it is survival, dignity and the only path towards a better future for her children. Her voice aligns with the spirit of the Sindh Women Agriculture Workers Act (2019), a law meant to protect and empower women farmers through fair wages, social protection, maternity benefits and recognition of their labour. Yet, like many other progressive laws, it still awaits full implementation in many areas.

Khadim Hussain Khaskheli’s story, from the village of Sirand in Sanghar, mirrors the struggle of thousands of Pakistani farmers. Born into a farming family, he spends his days cultivating land and fighting the unpredictable nature of agriculture. He spoke about the devastation of floods - how months of hard work disappear overnight - recalling how the 2022 floods drowned his standing crops and left him in debt.

Beyond floods, Khadim battles rising costs of fertilizers, pesticides, diesel and seeds. While expenses increase every year, crop prices remain uncertain due to the powerful middlemen system. Climate change has turned farming into gambling dry spells, sudden heatwaves and erratic rain patterns ruin entire seasons.

Khadim urges the government to provide post-disaster relief, quality seeds, affordable equipment and technical training. He emphasizes the need for crop insurance schemes, fair crop prices and reduced agricultural taxes so farmers can rebuild after climate shocks.

These stories are not isolated; they reflect the daily reality of millions of Pakistani farmers who contribute to national food supplies yet remain vulnerable to natural disasters, policy gaps and lack of institutional support.

The institutional challenge

To understand agriculture, we sought guidance of Mr. Sadiq. Muhammad Sadiq, an expert in water governance, farmer democracy and inclusion, explained the structural and legal challenges that hinder farmer representation in Pakistan. Under the Sindh Water Management Ordinance 2002, Farmer Organisations (FOs) are tasked with operational and maintenance responsibilities at distributary, minor and canal levels. Water Course Associations, as legally recognised entities at the grassroots level, feed into broader farmer organizations, which are supposed to manage water resources and farming infrastructure.

Sadiq highlighted that the system also includes Public Cooperative Entities such as Area Water Boards, designed for bulk canal operations and to allow public participation. Yet incomplete legislation and weak legal frameworks have prevented these entities from fully realising democratic representation. Alongside these, agricultural cooperatives and cooperative societies manage credit, marketing, fishing rights and livelihoods. Producer organisations, farmer producer associations, NGOs and advocacy groups also operate in the sector but coordination and democratic representation remain fragmented.

Currently, Sindh offers the most functional model for farmer representation. According to the Sindh Irrigation and Drainage Authority (SIDA), there are around 350 Farmer Organisations and 2,500 Water Course Associations representing the farming community. Punjab once had around 400 FOs, but many became inactive after provincial legislative changes and the dissolution of the Punjab Development Authority (PDA). In Balochistan, a few functional cooperatives exist, but on a minimal scale. Across the country, eight broad types of farmer organizations exist, but none function as fully democratic, representative body.

Sadiq also discussed the legal frameworks that reserve seats for farmers or labourers in provincial local government laws. Unfortunately, these provisions largely benefit large landowning families. Peasant and worker representation remains minimal, and farmers do not have equal influence in leadership selection. Crop-wise legislation, such as the Sugarcane Commission, exists but rarely provides genuine farmer representation. Large landlords often dominate these spaces, and even when some are committed, the voices of ordinary farmers remain unheard.

The democratic deficit

Sadiq highlights that the biggest challenge for Pakistan’s farmers is the lack of a democratic, accountable representation system. Current FOs, often limited to three-canal areas, fail to provide broad, inclusive representation. Sadiq suggests that if FO leadership from every canal were organized like bar associations, with elected chairpersons and vice-chairpersons at all levels, Pakistan could develop a truly democratic governance model for farmers. Unfortunately, such reforms have not been implemented, leaving farmers without meaningful institutional power.

Organisations such as Chambers of Commerce and Chambers of Agriculture operate under the Trade Organizations Act, 2013, with sections outlining licensing, scope and governance.

Similarly, Abadgar or Farmers Boards are voluntary associations registered under the Societies Registration Act, 1860, with regulations covering registration, property and dispute resolution. Yet despite these frameworks, farmers’ rights continue to be addressed in isolated silos rather than through cohesive, democratic institutions.

Pakistan has well-regulated boards for cricket, gymnasiums, and even rotary clubs, each with clear rules on membership and governance. But no clear legal structure exists to ensure that farmers - especially those from remote areas - can rise to leadership positions and represent their communities. Without such structures, fertile lands are lost to housing colonies, food security is compromised and policymaking remains disconnected from ground realities. Pakistan often faces paradoxical situations: exporting wheat and sugar despite shortages or importing vegetables from Afghanistan and Iran while local farmers struggle to sustain their crops.

Food security and

climate change

The vulnerability of farmers directly threatens Pakistan’s food security. Climate change, including unpredictable floods, heavy rains and shifting crop cycles, increasingly endangers production. Without strong, representative organisations, farmers cannot influence policy or access technical support to adapt to these challenges. According to Sadiq, only experienced farmers - rather than elites or political appointees - can lead institutions to ensure climate resilience, sustainable water management and food security for the nation.

A path forward

Sindh’s model under the Water Management Ordinance 2002 demonstrates that democratic farmer governance is possible. While it is not perfect, it provides a framework that can be expanded nationwide. Farmer organisations should be scaled up, aligned under unified legal frameworks, and given a platform for democratic elections. This would ensure that farmers from all regions - not just wealthy landowners - can participate in decisions affecting water allocation, crop policy and disaster response.

The government must also provide post-disaster relief, affordable credit, quality seeds, irrigation support and healthcare facilities for rural communities. Supporting women farmers, who often juggle cultivation, household responsibilities and children’s education, is especially crucial for inclusive development.

Institutionalising farmer representation, strengthening legal frameworks and investing in rural infrastructure are not just matters of fairness; they are essential steps to protecting Pakistan’s food supply, ensuring agricultural productivity and mitigating the effects of climate change.

Kissan Day is more than a symbolic celebration; it is a call to acknowledge the sweat, resilience and sacrifices of Pakistan’s farmers. Laws such as the Sindh Water Management Ordinance 2002, Trade Organizations Act 2013, and the Societies Registration Act 1860 provide frameworks, but without democratic implementation and policy support, these laws remain insufficient.

To safeguard food security, respond to climate challenges and respect the dignity of farmers, Pakistan must create truly representative institutions led by farmers themselves. On Kissan Day, let us remember that every grain harvested, every crop nurtured and every farm sustained is the result of relentless human effort. Protecting this effort is not just an economic necessity; it is a moral obligation.

The writer has over 20 years of experience as a development professional. She can be reached at [email protected]