From Shehzad Roy’s new song ‘Late Ho Gaye’ which calls out the burden put on children to the debut edition of LAAM Fashion Week in Lahore, here’s what made major culture news.

Shehzad Roy’s

‘Late Ho Gaye’

and the systems

responsible for childhood pressure

On World Education Day (January 24), Shehzad Roy released ‘Late Ho Gaye’, a satirical song that uses humour to call out something most Pakistani parents already know but rarely question: how academic pressure is deeply embedded in our cultural mores. What starts as a funny jab at overeager parents quickly reveals something deeper and uncomfortable for anyone paying attention to education and child development. The issue isn’t restricted to anxious parents. It’s a whole system that treats stress as normal before kids even start learning.

The video opens with an intentionally ridiculous question: Roy asks expecting parents if they’ve already enrolled their unborn child in school. He does so in a comedic manner, but there’s a real point underneath. Good schools that have set the benchmark for exemplary per-formance have an evaluation standard for what “ready” means, shifting the focus from whether a child is developmentally pre-pared to whether the paperwork got filed on time. For people who work in education, this scene captures how institutional dead-lines bulldoze over what children actually need.

The students featured in the music video are from Roy’s own Zindagi Trust schools, and that involvement gives the picture weight. When they talk, you hear layers of pressure that go beyond grades. Kids describe switching between languages at home and school, where discipline happens in one language and lessons in another. It’s not just a quirky cultural detail. It’s a cognitive and emotional burden that rese-archers now link to disengage-ment and low self-confidence in young learners.

The song also takes aim at tuition culture, showing kids crammed into extra classes before they’ve had a chance to eat, rest or just play. It’s a routine plenty of families recognise, but the long-term effects often get brushed aside. Educational res-earch repeatedly shows that downtime, unstructured time, helps kids regulate emotions and think creatively. But the video suggests that this time has been completely swallowed by an endless performance wheel.

There’s also a critique about distracted parenting. Screens replace conversations and kids get pacified instead of heard. For people who study these things, it points to a widening emotional gap in modern households where parents are highly involved academically but emotionally checked out. The pressure isn’t just about school. It’s relational, shaped by less time for real listening and connection.

What makes ‘Late Ho Gaye’ hit differently is that Roy doesn’t blame individual parents.

Instead, he shows how social competition, policy structures and elite school practices all feed into a culture where childhood becomes a race.

His closing message “to educate, not burden” reframes success as growth instead of constant comparison.

The response from public figures shows how widespread this anxiety is. Actors and creators like Maryam Nafees, Rushna Khan, Saboor Ali and Sarwat Gilani have echoed the message that childhood shouldn’t be controlled by admission calendars or social one-upman-ship. Their reactions reflect a shared understanding that the system rewards early compliance more than emotional readiness.

The way Roy sings is his recognition of music as it stands today. He isn’t singing. He finds a path between rap and pop, creating a sound that will appeal to old-school fans of his music and a newer generation that responds to rap as the only credible form of music nowadays.

As for the message behind the song, Roy’s work through Zindagi Trust gives it added credibility. His schools integrate music, chess and creative learning into academics, reflec-ting an approach that prioritises developing the child as a whole by going beyond rote learning and immersing them in creative activities. In that light, ‘Late Ho Gaye’ feels less like a protest song and more like a policy argument wrapped in a catchy tune.

The video works as relatable satire, but it also highlights how early institutional pressure has been normalised and how easily childhood gets warped by deadlines instead of develop-ment. Roy’s song isn’t just cultural commentary. It’s a reminder that real reform means more than changing the curri-culum. It means rethinking when and how we decide a child’s life is supposed to start.

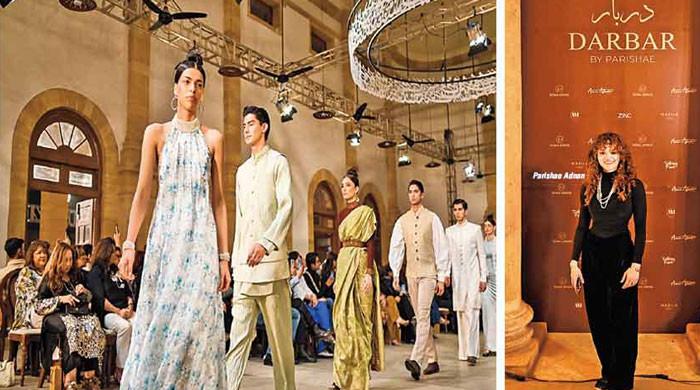

LAAM Fashion Week and the business of fashion

Pakistani fashion has spent years looking outward. Designers chasing international buyers, digital platforms pushing for growth and fashion weeks seeking global recognition. LAAM Fashion Week takes a different approach. It’s not trying to be the loudest voice in the room but a more considered one.

Running in Lahore from January 31 to February 3, it’s less about a splashy debut and more of a natural progression for the Pakistani fashion industry.

What makes it different is its structure. LAAM is Pakistan’s first fashion week where you can buy what you see, right there. It brings together couture houses, luxury prêt labels, high-street brands and manufacturers in one place to reflect how fashion actually works today. The focus is not on the glamorous runway and high fashion alone but taking it to the next and most obvious level: the consumer.

On the first day, the LFW Presents segment will not be about looking back with nostalgia but about remembering what matters. The showcase will bring together pieces that actually shaped how the country dressed and how it saw itself across decades. With over 28 legacy designers including Ali Xeeshan, Amir Adnan, Ammar Belal, Deepak Perwani, Elan, Fahad Hussayn, Faiza Samee, Feeha Jamshed, Generation, HSY, Huma Adnan, Hussain Rehar, Karma, Khaadi, Maheen Khan, Mahgul, Meeras by Nilofer Shahid, Mohsin Naveed Ranjha, Nomi Ansari, Rizwan Beyg, Saira Shakira, Sania Maskatiya, Shamaeel Ansari, Teejays, The House of Kamiar Rokni, Wardha Saleem, Zaheer Abbas and Zainab Chottani, this segment is about fashion’s living memory. This isn’t a reimagining filled with updated versions but an acknowledgement. These are clothes brought together because they left a mark and meant something.

But it’s not all haute couture. The week will also feature a curated selection of high-street, prêt and manufacturing brands such as Agha Noor, Allure by Izna Hamza, Amna Ilyas, Bin Tayyab, BulBul, Golmohar by Asif Chaudhry, Haseens, Kiara, Kibo, Lulusar, Meerak, Meeral, MISL, Mohagni, Mushq, Panache App-arel, Pehnawa by Bin Akram’s, Rang e Haya and Urge Pret, reflecting Pakistan’s thriving and increasingly sophisticated fash-ion scene.

These collections will be available for purchase immedi-ately after their shows.

Participating brands have gone through the Ramp Readi-ness Programme, which add-resses a persistent gap within the industry. Great design doesn’t automatically mean a business that lasts. Designers will get sales data, traffic insights and per-formance analytics, allowing creative decisions to be shaped by what people actually respond to rather than guesswork.

Luxury and bridal collections will be released in phases, timed with how long they actually take to produce. It’s a model built around what’s practical rather than what generates the most noise.

As Maheen Kardar of Karma told Instep, “LAAM Fashion Week’s runway-to-e-tail approach changes the game. As a designer and Executive Design Director, I’m thrilled that our collections can be experienced in real-time by everyone, not just those in the room, making fashion immediate, immersive and inclusive.”

From there, the focus will shift towards the future with LFW Hot List, a platform for recent graduates from the Indus Valley School of Art & Archi-tecture (IVS) and the Pakistan Institute of Fashion Design (PIFD). Ten capsule collections, developed through institutional collaboration, will mark the shift from classroom to industry. The collections will cover a wide range, from NuXaan Lai’s take on identity through embroidery and quilting to experiments with denim, leather and sculptural forms that imagine future cities, explore emotional transformation and redefine hybrid streetwear. The focus isn’t on rushing things. With no participation fees, a dedicated spot in the e-store, mentorship and minimal or no commission periods, the setup is designed to support careers, not just offer a brief moment in the spotlight.

Day 1 of LFW Hotlist will extend its support for emerging talent beyond fashion. Pakistan Idol’s Top 16 finalists will perform their critically acclaimed medley, creating a moment where young designers from IVS and PIFD and rising musical voices share the same platform. It’s a collaboration that feels natural, bringing together diff-erent forms of craft and creativity under one roof.

A significant moment will arrive with LFW By Invite Only. This season, it is spotlighting Rizwan Beyg. His collection, Jashan, will pay tribute to the craft of rural women from Southern Punjab through the Bunyaad initiative, using handloom tissue nets, chiffon and silk in soft ivories and muted shades. The collection doesn’t try to dazzle. Instead, it reinforces the idea that real legacy isn’t about grabbing attention. It’s about showing up consistently and respecting the work itself.

The scale is global by design. The event will be livestreamed across more than 120 countries, reaching audiences in over 7,800 cities. But the goal isn’t just to put on a show. The thinking behind LFW comes from learning what didn’t work before.

As Saad Ali, Founder & CEO of Design651, Co-Founder of LAAM Fashion Week and CEO of PFDC told Instep, “Past fashion platforms, particularly PFDC, played a foundational role in institutionalising fashion weeks in Pakistan. One of the most important lessons from that era is that visibility alone isn’t enough for a platform to endure.”

Arif Iqbal, Co-Founder & Chief Executive Officer of LAAM and Co-Founder of LAAM Fash-ion Week, reframes who the audience even is. He told Instep, “Your front row isn’t just buyers and editors any more. It’s millions of consumers watching, engaging and ready to act.”

Whether that engagement translates into actual purchases remains to be seen but the infrastructure is finally in place to find out. To most people, LAAM Fashion Week might just look like another event on the calendar. But if you look closer, it’s a change in how the industry sees itself and who gets a say in what happens next.